Microsoft is planning an overhaul of our Office documents, weaving live data into the once-static fabric of our Word files and Excel spreadsheets. It’s a bold experiment that could kill the very definition of an Office “document”—but it could also spell the rebirth of Microsoft’s productivity suite in the age of cloud-driven collaboration.

At its Build 2013 conference in June, Microsoft evangelized tools that will enable app developers to automatically use Bing’s search capabilities in documents—for example, they might enhance a travel guide with live demographic information on Belize. And Microsoft’s new PowerBI tools, announced Monday at the company’s Worldwide Partner Conference, can import data from both public and private sources to provide more up-to-date context in documents.

Both developments reveal a sea change in the way we’ll interact with Microsoft Office in the future. In the current regime, you create an Office document, save it, and then email it to a colleague, who quite likely prints it out. Indeed, the documents we create today represent just a slice of information within a brief snapshot of time.

But all this can change once Office begins hooking into living data. Office docs won’t simply document the past: They’ll also accurately reflect the ever-changing present.

”In the past, people would send around a static spreadsheet or a static PDF, with static data,” Kelly Waldher, director of Office 365 product management for Microsoft, said in an interview. “What PowerBI offers with Office 365 are a couple of new elements: real-time updates and real-time data.”

Microsoft has connected its SQL Azure cloud database to SharePoint Online, creating shared PowerBI workspaces that partners and coworkers can access, Waldher said. With a live data source powering the document, you can be sure you’re getting the most up-to-date information—and therefore the best information to base decisions on. This model assumes that documents will no longer be printed out or archived in a dead, static format, since doing so would rob them of the contextual intelligence that live data offers.

Microsoft understands that its vision will first be enabled within business environments, where enterprise tools can make sense of big data. But it’s not hard to imagine a future where a college paper on climate change might feature an interactive map that plots average mean temperatures for various cities. With consumers increasingly turning to the cloud for data storage, people will place less value on older, static documents, and more on up-to-date responses to changing conditions. That preference could extend way beyond Microsoft, and into the greater information ecosystem as a whole.

At Microsoft’s Build 2013 conference, Gurdeep Singh Pall, corporate vice president for Microsoft’s Information Platform & Experience group, announced “Bing as a platform,” taking what we know as Microsoft’s search engine, and making it available to developers as a third-party API. “The unbounded knowledge of the Web is now available to your applications,” Pall said.

One of the tricks Microsoft executives showed was the capability to scan a block of text for keywords—such as “Valencia, Spain”—and hotlink the text to Bing-curated data. It exemplified how we might take an otherwise static document and enrich it with the Web at large.

What ‘business intelligence’ actually means

This past March, Microsoft launched a preview of its Data Explorer tool, which allowed users to pull data from various sources and put it into Excel documents. For example, you could tell Excel to pull a compilation of credit card complaints from data.gov, or to pull a list of World Cup winners from a Wikipedia article. By itself, that capability wasn’t terribly exciting.

But on Monday, Microsoft renamed Data Explorer as “Power Query,” and surrounded it with a number of equally robust tools: Power Map for geolocating data; Power Pivot for flexible data models within Excel; and Power View, which allows Excel to parse data itself and to attempt to present the most relevant views automatically. Microsoft has also developed a number of BI “live sites” where customers can interact and share data.

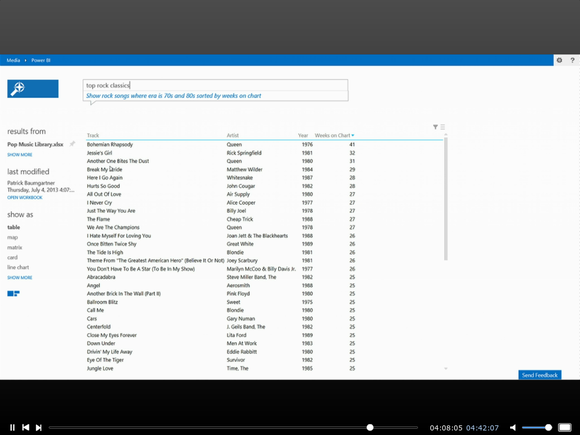

Microsoft corporate fellow Amir Netz did a wonderful job of putting it all in context. (Netz’s presentation is archived here; fast-forward to 4:03:05 for the BI demo.) In a demonstration that used a database of popular music as an example, Netz typed in “top rock classics” as a query. The responses were automatically sorted into a track list from the 1970s and 1980s, cross-indexed by the number of weeks each song appeared on the chart. Highlighting certain words auto-suggested other choices. Highlighting “songs,” for example, suggested a list of “albums” with the same characteristics, providing avenues for further exploration.

“When I typed ‘top rock classics,’ it understood I meant rock,” Netz said. “And when I said ‘classics,’ it understood that I meant music from a certain era—the ’70s and the ’80s—and not the 1950s.”

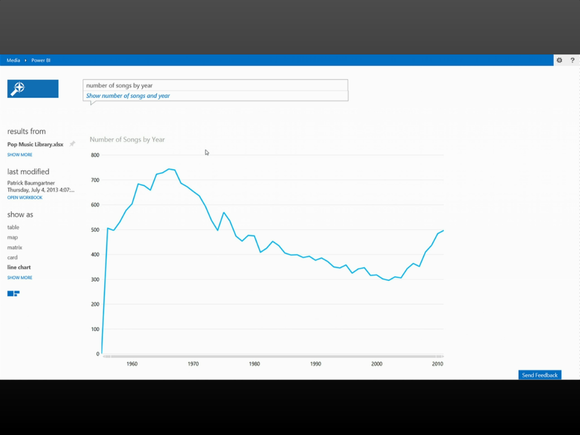

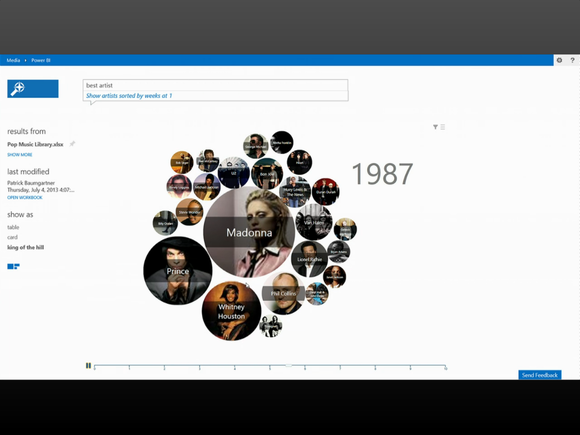

Asking for the number of songs by year automatically generated a line graph tracking how the number of popular songs people listened to decreased between 1970 and 2000. Netz finished up by asking PowerBI to determine the best song of all time (Jason Mraz’s “I’m Yours”) and the best artist of all time (Mariah Carey). This assessment was based on what the database “knew” about each artist. Netz finished with a “king of the hill” visualization that tracked which artist dominated during which year.

”It is the beginning of a conversation with PowerBI,” Netz said, as he input a query into the search box.

Queries, not documents?

If Microsoft’s vision takes hold, static documents loaded with static data will seem increasingly irrelevant as time goes by. Imagine a PDF from your travel agency that answers the basic question, “What are the best countries for me to visit in Europe and the Middle East for a summer vacation?” In today’s version of the document, the answers are fixed. But we should be able to ask that query at any time, and receive answers that reflect a multitude of variables—exchange rates, hotel availability, weather, and political stability.

We already live in a world where the living Web and other information sources dynamically respond to changing conditions. Take, for example, the Max tool from Netflix, which asks you questions to determine which movie you want to view. The Netflix database constantly updates itself with new movie titles, and uses information gleaned from everyone’s user searches to make other recommendations.

So at what point will traditional Office “documents”—spreadsheets, Word documents, and the like—begin to go away, victims of their own irrelevance? We don’t need to store Word documents that list the 20 bands that have the most number one hits, because that information is already stored in a database somewhere. But we will store our own analyses that machines can’t provide: the fable of Beowulf and Grendel analyzed in a historical context, for example.

If Microsoft’s vision of live, connected files becomes reality, the document of tomorrow could evolve into a framework, a predefined query. We may not know what the 100 highest-grossing movies of 2010 through 2020 will be, but we can create a document that’s preformatted to access that information—and to do so in a way that will let us quickly determine whether a sequel is primed for box-office success.

If that happens, seemingly disparate technologies—Office, Bing, and Azure—will become more closely tied to one another. And what we mean by “documents” will move far beyond today’s traditional definition.

As a result, live data sources will serve as increasingly tangible barriers that prevent data from migrating off of Office to other platforms. Indeed, while Google Apps and Apple’s iWork might let you open Microsoft’s PowerPoint format, you may not find the same level of support for Microsoft’s highly involved living-data technologies. For business users, at least, it may pay to remain under Microsoft’s umbrella.

----------------------------- collected information from: pcworld --------------------------------------------

MICROSOFT

MICROSOFT

No comments:

Post a Comment